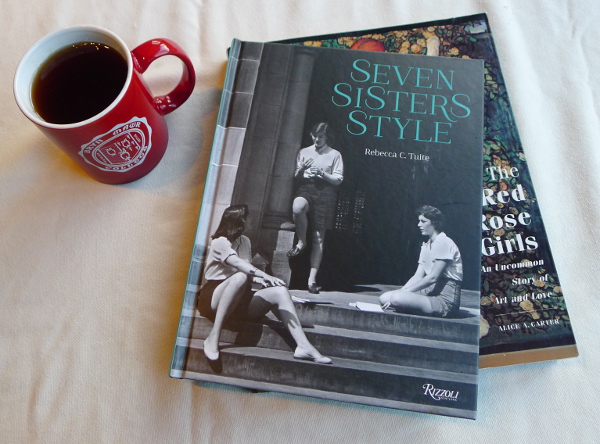

Putting on my tatty Bryn Mawr academic robe here to review a book: Seven Sisters Style, a recent volume about the clothing worn by and inspired by women university students at Seven Sisters universities in America.

You may be familiar with a Japanese photo book, Take Ivy, compiled by four Japanese photographers charmed by the style of young male Ivy League students in the 50s. While their contemporaries were making monster movies, they were at the campuses that incubated the academics for The Manhattan Project. A different way, perhaps, of capturing their post-nuclear monsters – the college sweatshirts and J. Press button-downs are described in brief captions with anthropological reverence and puzzlement. Take Ivy‘s combination of crisp photographs and otherworldly captions made it a long-term classic amongst style historians.

It’s taken another outsider to bring us an intended companion volume. The glamorous author of Seven Sisters Style, Rebecca Tuite, is originally from the UK and spent some undergraduate time at Vassar, the Seven Sisters university in Poughkeepsie, New York. And Vassar has been the focus of much of her fashion history study.

The Vassar connection is important. Through the history Tuite presents, Vassar also comes across as the most troubled locus of media fever-dreams about the American women’s university student. While a Bryn Mawr College article in Life magazine cemented the school’s reputation for “intensity”, a Vassar-focused article in 1937 sparked a fashion craze. These Vassar depictions reached their film zenith with Marilyn Monroe impersonating a Vassar student in Some Like It Hot and their print apogee with the novel The Group in 1963.

Back to the book: this slim volume is a history of clothing styles on Seven Sisters campuses from the 1920s through the late 1970s, far wordier than Take Ivy. These clothes have meaning: they were what women choose to wear at a time when women began to live independent, modern lives. At times Tuite’s connections between wider fashion trends and the university students come across as convoluted, and at other times, a tantalizing sentence and a small photo left me frustrated. Also, photo choices are a problem. In the second half of the book, most of the images aren’t from Seven Sisters schools or students at all, but from journalists visiting the schools or from modeled advertisements for clothes “in the style of.” Perhaps these were chosen to show that The Styles Truly Were An Influence – or perhaps because they tended to feature conventionally pretty students or actual models.

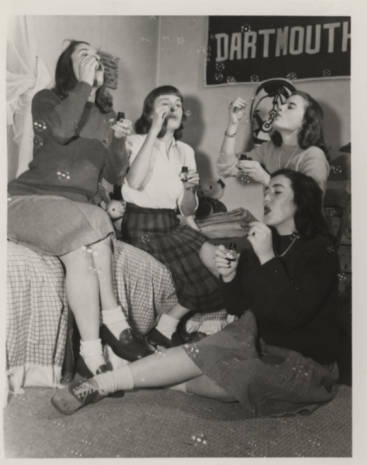

One of the book’s images that troubled me – Mount Holyoke women in 1945: posed and heteronormative (note the Dartmouth banner): in no way representative of the scintillating Mount Holyoke women I know.

Is Tuite’s book made, or undone, by her fondness for the proper, public, preppy side of Seven Sisters style? She’s certainly hit a nerve with everyone who grew up far away from American preppy but dreamed fond dreams about letter sweaters and camel coats. Dames in ragged racoon coats and dungarees are mentioned – they have to be, they were so prevalent – but Tuite only selected photos of them if they were pert-nosed or (with a caption exhaling a sense of relief) particularly neatly groomed. Instead, she lingers most lovingly over the idea of a Vassarite being swept away to New York City on the weekends, dressed in a clever town suit, with a valise containing a demure yet alluring ballgown.

Ahem. The Seven Sisters STILL ARE, Tuite, not WERE…

Tuite’s edited evocation of East Coast prep is so wildly successful that I – with my personal feelings about preppy after growing up in New Haven, CT – felt rebellious and prickly while reading it. After my first browse, I ran out to a local thrift store to feel like my present-day self again. No, wait, that’s where I shopped when I was at Bryn Mawr. AUGH!

An entire perplexing chapter is devoted to the designer Perry Ellis and … I picked up this book to see real Seven Sisters style and history and we were, it seemed, all out of that after Love Story came out.

Another image from the book that troubled me – the abbreviated preppy clothes, the pose, all summing up the ideal and inviting the viewer to see a (Vassar!) student’s body. The fantasy manifest.

The end result is a historical and social overview overwhelmed by the preppy dream: images of autumn leaves, sweaters, gowns, print books, and social status mingled with academic freedom. I truly wish I’d enjoyed this book more. Am I frustrated about the book itself, or about the perceptions of Seven Sisters universities that Tuite has revealed? Can one only enjoy this book if one hasn’t also read The Bell Jar? Tuite is at her best on Vassar, so an entire book by her on Vassar style and women would be a fascinating read. But the allure of the preppy dream led her to decline fully exploring actual Seven Sisters style and how it reflected the fun, freedom, stress, and variety of the students themselves. Ourselves.

I’d like to see a follow up by somebody less prep-invested that focuses on the style outliers and oddities and otherness consistently sheltered by these institutions. Barnard beatniks and Bryn Mawr medievalists, the millenial students going to class in their pjs (acknowledged yet dismissed by Tuit herself), the emerging trend for university-themed tattoos, and the students turning the style lens back on themselves in student-run style magazines.

Also, there was a Bryn Mawr blazer? WHERE IS MY BRYN MAWR BLAZER?

Bryn Mawr College imagery of actual students: simply irresistible. And, that blazer!

1 Comment so far